Nationalism is the force that has brought the world to its modern form. It has claimed to alter the social and political structures in vastly different forms from their previous versions. The concept of nationalism has never gone out of vogue since its inception. However, since the beginning of the twenty-first century, myriad factors such as populism, terrorism and identity politics have led to a resurgence of nationalist fervour across the globe with varied intensity. Nationalism gives the individual a powerful sense of belonging to an ‘imagined community’ (Anderson 2016). The various theories of nationalism focus on the factors leading to the origin of nationalism. However, the critical question is how these identities are forged, sustained and reproduced over time.

The modernist theory of nationalism, owing to the contributions of Gellner and Hobsbawm, argues that nationalism is a novel form of belonging. The nation came into existence for the needs of industrial societies, which increased social mobility, led to urbanization, and a demand for standard education (Smith 1969). On the other hand, the primordialists, such as Edward Shills and Clifford Geertz, argue that nations are natural units. People are born with group identities based on ethnicity, language, race, religion, etc. (Smith 1969). Anthony D Smith tried to bridge the gap between the modernists and primordialists. Smith, in Myth and Memory of the Nation (1999), focuses on ‘ethno-symbolism’. Smith’s ethno-symbolism contends with the modernist idea of Hobsbawm that nationalism is a product of modern conditions of industrialization, urbanization and standard education but differs in the mode of its making. Following the primordialist line of argument, he argues that the roots of nationalism lie in the myths and the memories of the past (Smith 1996). Smith’s approach to nationalism supported a nuanced understanding of culture and history in the making of modern nations.

Nations often look at glorious memories of the past that aspire for a shared future and destiny. However, in the lack of clear access to history, the past is often mystified around myths. Myths are seen as agents of imagination, making them visible and fixed in memory (Vecchi 2018). Myths do not have to be real, but they acquire a certain connection with reality. They represent a deliberate manipulation of events and flattening of complex narratives but not necessarily the distortion of historical facts. Verovšek says that myths are used to mobilize memory (Verovšek 2016). He continues with the argument that often, manipulation of memory as myths are used to push a certain narrative about the issues of the present.

The exceptionalism of culture, religion, race, and nation are often the most common myths found across time and space. As Smith suggests, it is hard to distinguish memory from myths. Their dichotomy and the accordingly settled histories of the nation-state seem inadequate to understand and act upon secularism, equality and justice. Between the two extremes lies an intermediate settlement formation where myth and memory functions coexist without distinguishable boundaries. Such formations evolve due to a complex set of historical, cultural, economic and nationalist forces. Under this axion, it is acknowledged that the relation of the two follows an interlinked curved.

The narratives play a significant role in consolidating this interconnectedness between myth, memory and the national. They are often the memories of an ancient past or the glorified struggles of the recent past, as found in the national narratives of post-colonial societies. The memories act as forces that weave together the communities and create the difference among the outsider communities bringing the ‘us’ and ‘them’ categories into the discourse. The memories do not represent the past itself but rather a past that acquires a contemporary character. In the same manner, national myths are also glorified and romanticized versions of a nation’s past, often a fictional narrative, other times distorted and mystified historical facts.

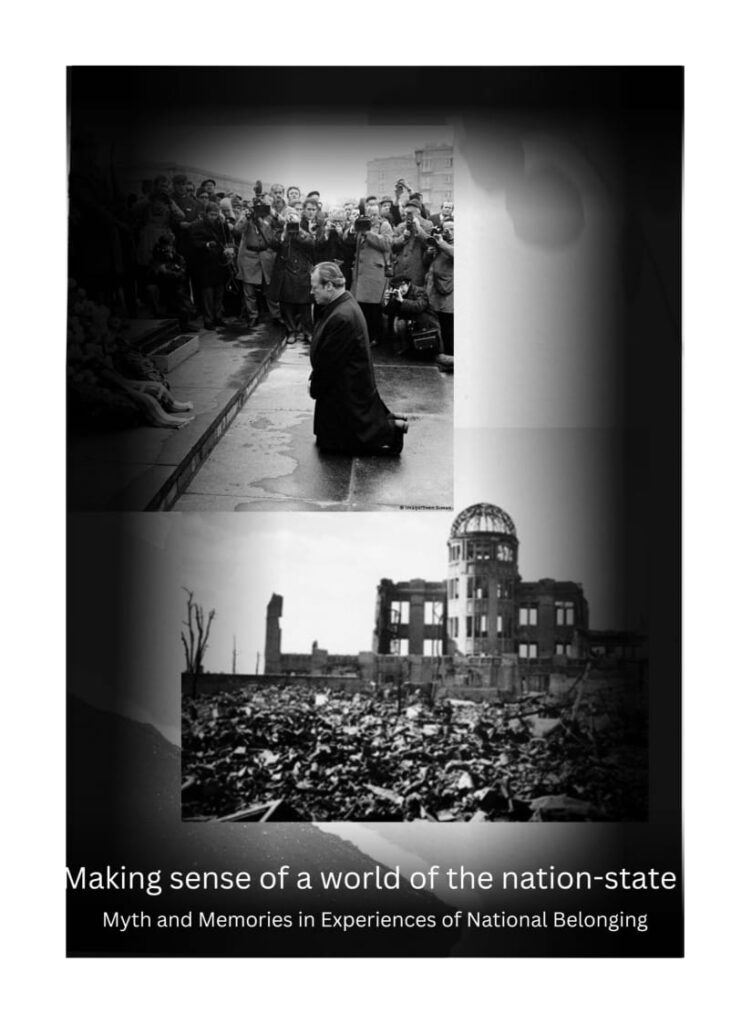

In Smith’s characterization, memory and myth go together and lose individual distinctions. They serve as the foundation for one another. Both entities create a collective sense of identity. However, national myths or memories represent the dominant narratives of any nation. Dominant narratives are defined and made of some degree of fabrication, exaggeration, and neglect of memories of marginalized communities. The narratives of heroism or victimhood act as a political tool for the national elite to remember and justify certain historical narratives. For illustration, the Japanese state instrumentalized the memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to create a myth of victimhood. The myth neglects the mass crimes of imperial Japan against the South East Asian countries.

In conclusion, the analytical categories of myth and memory prove hard to be distinguished in the narration of national belonging. However, both serve as instruments for streamlining the state’s hegemonic narratives and challenging them.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. 2016. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso Books.

Smith, Anthony D. 1969. “Theories and Types of Nationalism.” European Journal of Sociology 10 (1): 119–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975600001764.

———. 1996. “LSE Centennial Lecture: The Resurgence of Nationalism? Myth and Memory in the Renewal of Nations.” The British Journal of Sociology 47 (4): 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/591074.

Vecchi, Roberto. 2018. “Mythology and Memory.” European Research Council, November.

Verovšek, Peter J. 2016. “Collective Memory, Politics, and the Influence of the Past: The Politics of Memory as a Research Paradigm.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 4 (3): 529–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2016.1167094.