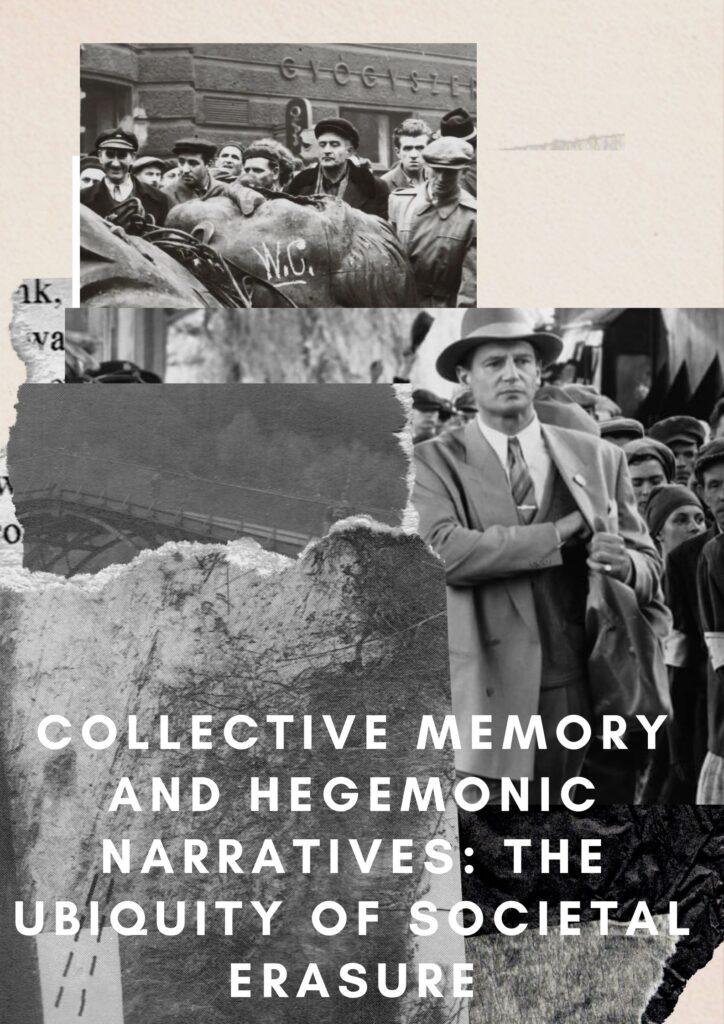

This poster brings into focus two things. The fallen statue of Lenin highlights the contemporary contestations of history. It aims to delegitimize certain ideals of the past that do not align with the present aspirations. Removing the statues of Lenin does not wipe out the history of authoritarianism in Russia. However, it condemns an uncritical acceptance or any degree of glorification of it in the present. The story of Oscar Schindellar in the Holocaust is precisely the opposite of a bystander. The poster dwells on the significance of the role of bystanders in history in keeping the authoritarian regimes and brutal genocides, where even one man can make a difference in thousands of Jewish life.

Collective Memory and Hegemonic Narratives: The Ubiquity of Societal Erasure

The modern historian is Sisyphus. She rolls the boulder of neatly organized knowledge of the past to the top of the mountain, just for it to roll back down. There can be two ways of looking at it. Either history is rewritten again and again within our civilizations, or there are always specific revisions required. The boulder returns for the historian to make necessary revisions, aligning with the present vision of the past.

Our knowledge of history is relatively meagre compared to the complete history of human existence. The written and Oral histories are all parts of knowledge of human civilization, seen through the needs of the present narratives. These narratives result from overt erasures of duplicitous complicity, fragmented resistance, the passivity of bystanders, and covert decisions of binary constructions of historical heroes and villains.

In the turbulent times of ‘black lives matter’ (from here on BLM) and revisiting the histories of colonialism and colonial heroes are some of the significant points of contestation in collective memory today. In conjunction with the power hierarchies encoded in history and their continued presence, the contestations also emanate from the collective memory of subjugation and historical injustices. Memory makes the roads for the narratives to be constructed, debated, marginalized, and hegemonized. Additionally, the myths of solidarities and narratives of the collective memory form nationalist ideals induced with remarkable quality of sacredness and untouchability.

The past is only stable till there are rebellions and political dispensations, like BLM and international conflicts like the Ukraine-Russia war, that demand history-memory narratives to be revisited. Therefore, becoming part of critical junctures, such events lead to a revision of societies’ imagination of the past. Critical junctures are strategic points in history where the decision-makers have the agency to establish the course and patterns of events in popular historiography, push narratives, and construct myths which would characterize society and the nation in the future.

The central part of the argument is human agency in making these patterns. The Human-agent, characterized as Dasein in Heidegger’s Being and Time, is a situated being in the past. Dasein is running to the future while continuously spiralling back to the past. The past becomes the determinant of the future. However, Heidegger ignores the weight of the present on the interpretation of the past. By incorporating Merleau Ponty’s critique of Heidegger, the present would appear as mediating between the two.

Our future will only reflect what we have acknowledged in the past. The historical contestations of the present embark on a debate over these acknowledgements, breaking into mainstream and marginal discourses. The discourses pertain to the social understanding of the individuals, the place of communities in the social hierarchy, and the outlook toward knowledge, religion, and politics. The character of the society would be dynamic but stable within the structures of their time, reflexive of its temporality.

The historical contestations occur against the process of erasure. The marginalized memories and narratives compete and challenge the stream of the dominant discourse. The monuments and the commemorations of the present reflect a past that upholds the values we cherish, and the toppling of statues, rebellions against commemorations like Columbus Day, and the demands for new commemorations reflect the erasure. The erasure of those that have been marginalized or forgotten in the making of the dominant discourse.

In the political memory and aesthetics of care, Mihaela Mihai traces a double erasure. Creating dominant narratives destroys “plural spaces” and fills them with one type of noise. The hegemonic narrative of collective memory colonizes the hermeneutic space of society, resulting in closed horizons. The ideological commitments of the decision makers, the power hierarchies, and structural capabilities and constraints creates erasure. Under authoritarianism and colonization, the first erasure absolves the communities of complicity with the violence in the pervasive structure.

Meanwhile, the second erasure does not come from negligence and absolution of society. It is a positive intervention in making the idolized figures, usually a singular male resister, subject to societal worship. The resister and the bystander are purged from their cowardice, occasional complicity and silence. The political space of social imagination is narrowed to the grand modalities of resistance. The heroic actions are only idealized visions of resistance. The sacredness and purity image of the hero leaves no space for the impure, fearing resister. In this atmosphere, the closed space reproduces these same visions over time.

Thus, the national memory becomes an ‘us’ and ‘their’ literature, where the perpetrators and the victims, who later become the heroic resisters, are marked. Whoever does not fit in this characterization is marked unfit for honourable history and is erased. The erased narratives lead to a continuation of structure. The “legacies of the forgetting” carries the inequalities and perpetuate them in racial, caste, and gendered hierarchical relation. Political visions and political practices discursively and formally reproduce the hegemonic narratives. They marked the historical conjunctions; in the first erasure, the naturalized ideas deluded the practices before the rupture. This process results in silencing the dissenting voices about what happened. Moreover, it reflects the material patterns of exclusion of the past and their systematic negligence in the present. The unwavering acceptance of a narrative will result in silencing histories and continuing silence on the same atrocities in the present and the future.

The political space of a community should embody a space for the silences, the complicities of people in the subjugation of their compatriots in colonized societies and the fragmented resistance under authoritarian governments. A society’s political imagination is revised to situate the non-perfected accounts of hegemonic narratives, a site of double erasure. Both the resistance and the complicity are impure. It is challenging to draw a clear line between good and evil in history, which we see in today’s toppling statues of political leaders. The removed statues symbolize a space for bringing back the marginal historical narratives eyeing the different imaginations of the future and visualizations of the past.

References:

Aho, K.A., 2010. Heidegger’s Neglect of the Body. Suny Press.

Capoccia, G. (2016). Critical junctures. The Oxford handbook of historical institutionalism, 89-106.

Desai, S. (2020, July 13). Of Memory and Erasure. The Times of India.

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/Citycitybangbang/of-memory-and-erasure/

Mihai, M., 2022. Political Memory and the Aesthetics of Care: The Art of Complicity and Resistance. Stanford University Press.

Image credit:

The New York times

amctheaters.com