The past is not dead. In fact, it is not even past.

William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (1951)

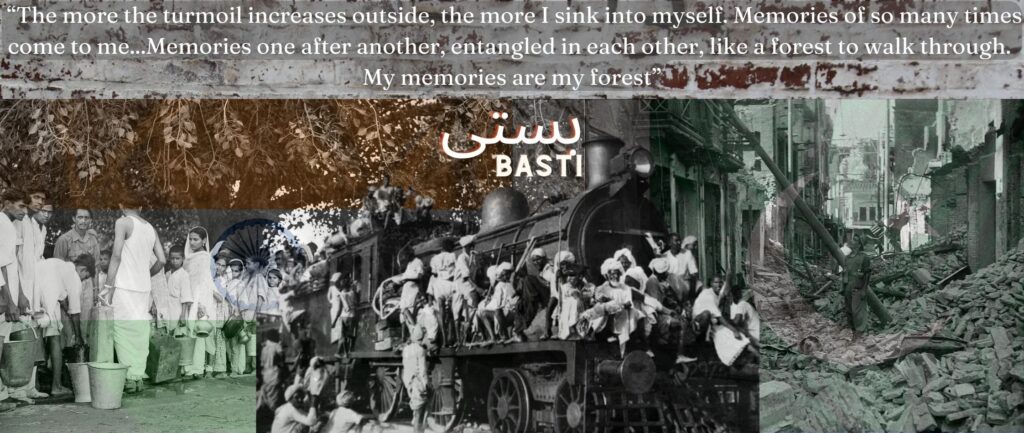

Amidst the clamorous turbulence, turmoil and tumult of the Partition, Basti sits in a sombre, solemn, albeit ruptured, landscape. At the outset, the reader encounters a mythic, almost mystic echo-chamber of voices of a reminiscing history professor, Zakir, the novel’s protagonist. Sleep brings to him dreams of a world passed and in passing, he wakes to a new homeland, a new settlement, a new basti. Cloaked in sheets of nostalgia, displacement and ruptured continuities, Zakir’s tomorrows are taken care of by his yesterdays. Zakir notes, “I am on the run from my own history, and catching my breath in the present. Escapist. But the merciless present pushes us back again toward our history” (Hussain 68). He who remembers lives unaccommodated. For Zakir “the outer world had already lost its meaning” (Hussain 46) and it was not very often that he breathed “the air of his own time” (Hussain 45).

Hussain weaves realist imagery, mythology and Indian, Persian and Arabic folklore to create a non-linear narrative. Zakir’s turn to the past—historical and mythological—is a means to centre the decentered self that finds itself in a continued state of exile in memory and in real time. Zakir sought to “turn to the temporal event of Prophet Mohammad’s hijrat from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE into an archetypal event of renewal, an epiphany that could enact itself again and again across time and history.”. The South Asian Muslims were given the opportunity to constitute a distinct identity for themselves post the Partition of India, but this also implied a psychic schism in the displaced communities whose identities were already tied to an earlier prelapsarian, paradisiacal Rupnagar, a metaphor for undivided India (Memon). The dislocated migrant “sees things in terms of both what has been left behind and what is actually here and now.” This results in a double perspective that never sees things in isolation (Said 375). This plurality of vision gives rise to simultaneous dimensions of reality and truth and instils itself as a condition of the mind. Exile is an endless paradox of looking forward by continuously looking backwards.

Jean-Paul Sartre stated that the imagination frees a person from inhabiting any single given reality but Zakir’s imagination is exilic. “The more the turmoil increases outside, the more I sink into myself. Memories of so many times come to me. Ancient and long-ago stories, lost and scattered thoughts. Memories one after another, entangled in each other, like a forest to walk through. My memories are my forest” (Hussain 8). The wilderness of the forest represents an aspiration to be lost, and consequently found. Alok Bhalla opines that, “Nostalgic remembrance is for him a form of retrieving knowledge about those modes of living from the past which could be used for the redemption of future time” (Bhalla 22). Hussain’s narrative functions at three levels; (1) Personal Memories, (2) Cultural-political life of the sub-continent before 1947, (3) Imaginative Reconstruction.

Abba Jan’s repetitive recital of the Khilafat Movement and Maulana Muhammad Ali’s “cultured speech”, Ammi’s constant worry of Khala Jan and Dhaka, and Khvajah Sahib’s glorification of the curfew that followed the Jallianwala Bagh massacre invite the reader into the territory of an entire generation’s failure to assimilate with the promised land. The memory of a home that exists nowhere but in memory pervades all conversations symbolising a rootedness in the past and its presentness. When presented with the tumult of the present, Abba Jan turns to the Holy Quran for answers. Zakir’s statement “Abba Jan still hasn’t emerged from the time of the Khilafat Movement” (Hussain 21) mirrors his own state of being—a being enmeshed in myth and memory.

The Qissa tradition is invoked in the text with oral story-telling and performativity that fuses the local Punjabi tradition and the migrant culture from the Arabian peninsula and contemporary Iran. The Jataka tales and Panchatantra fables provide a fertile ground for the germination of Zakhir’s imagination. These are supplemented by surrealist, mythic allusions bearing a postmodern impulse, that registers itself in the dream sequences throughout the text.

The Chinese-box narrative contributes to the polyphonic aspect of the narration which psychoanalytically unearths the mind. The transitions from Zakhir’s imagination to reality, from fiction to fact are seamless to the extent that the readers find themselves manoeuvring a cultural labyrinth. This endeavour of encapsulating civilizational memory, according to Aamir R. Mufti, “provides us with the fragments of a culture’s history that modernity has firmly set on the road to oblivion.”

Time in the novel expands and contracts according to the narrator’s will and at times “every action in that town seemed to be spread out over the centuries” (Hussain 8). Time, here, is a cultural continuum, rather than a disjointed moment, “an ebbing river that flows in and around consciousness of characters compelling the reader to do the same” (Ahmed 35). The temporal reality is in stasis which facilitates an archetypal consciousness but it is haunted by a modern existentialism. The collapse of the cruelty of impersonal empirical time allows Zakhir to reminisce about Sabirah, his childhood friend and romantic interest, whose presence in his life and the text remains tantalisingly ambiguous. Sabirah is a memory, a reminder of the rift between the two newly formed states but she is also a moment of reconciliation. Towards the end of the novel, Zakhir decides to write to her, bridging the gap between the memory of the woman and the materiality, closing the rupture between the states.

References

- Ahmed, Nida. “Consciousness of time, history and myth decenter the narratives of Basti and The Sleepwalkers to create modernist texts that resist neat closures.” International Journal of English Research. Volume 5; Issue 4; July 2019; Page No. 33-35

- Bhalla, Alok. Partition Dialogues: Memories of a lost home. New Delhi: OUP, 2007.

- Hussain, Intizar. Basti. New Delhi: OUP, 2007. Trans. by Frances W. Pritchatt, 1979. Print.

- Memon, Muhammad Umar. “Partition Literature: A Study of Intizar Husain.” Modern Asian Studies, 14,3, 1980.

- Said, Edward W. Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. 2000.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. The Imaginary: A Phenomenological Psychology of the Imagination. Translated by Jonathan Webber. London and New York: Routledge. 2004.