Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?

Derek Walcott, The Sea is History

Where is your tribal memory?

Sirs, in that great vault.

The sea. The sea has locked them up.

The sea is History

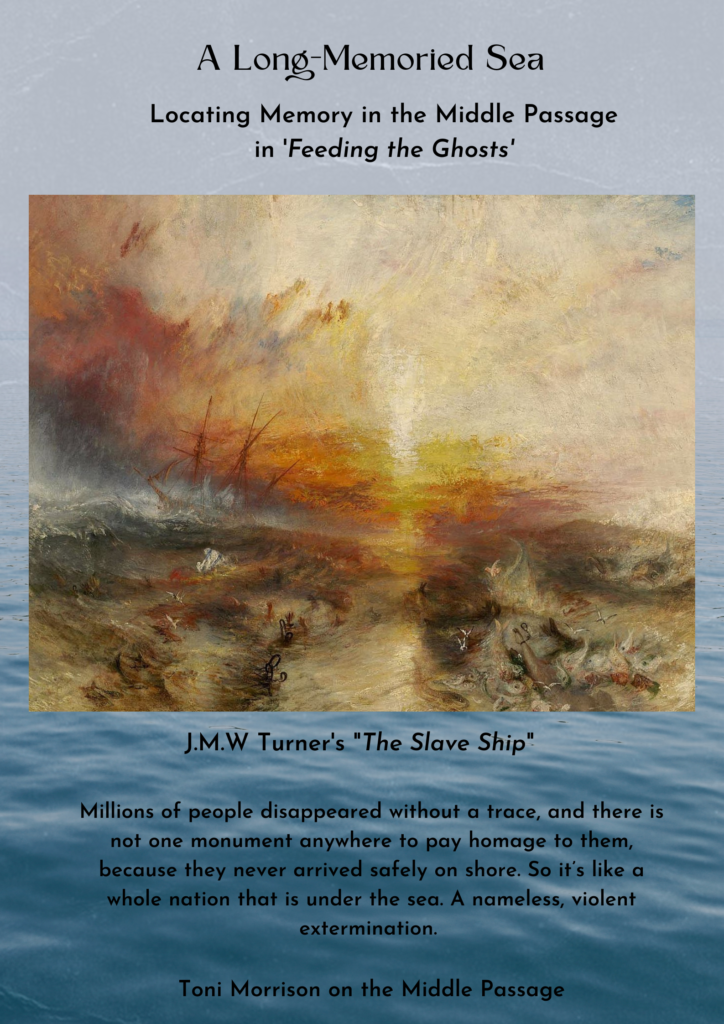

Dubbed as a historical revisionist novel, Feeding the Ghosts is Fred D’Aguiar’s fictionalized account of the infamous Zong slave-ship massacre, an incident where more than 130 enslaved Africans aboard the Zong were declared ill and systematically jettisoned into the Middle Passage in order to claim money from insurers. Feeding the Ghosts is a neo-slave narrative which remembers the gruesome incident not only for its contribution in propelling the abolitionist movement into public light, but also acts as a literary homage to the countless undocumented men, women and children who lost their lives to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, a “nameless, violent extermination.”1 (Carabi 38) The author positions the narrative around the fictional Mintah, a Fetu slave girl who had climbed back on board after surviving the jettison and had unsuccessfully attempted to incite an insurrection against Captain Cunningham. Inextricably connected to the ones who perished in the Middle Passage through their shared oppression, the text then becomes Mintah’s project of remembrance and her attempts to cope with the trauma of survivor’s guilt.

The sea of the Middle passage, which unanimously stands for the brutalities of the transatlantic slave trade haunts the collective imagination of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. The arduous journey through the Middle Passage from their homelands as part of the triangular slave trade was one that not many captives survived. D’Aguiar, in an interview with Joanne Hippolyte spoke of the sea and its resonance in Afro-Caribbean literature as a stand-in for the Middle Passage. He called the water “a shifting library of sorts” (Hyppolite 4), a geography onto which memory could be inscribed.

D’Aguiar leans heavily into the symbolic potential of water and describes it as a phenomenon of tremendous strength, a devastating force that is hostile, deadly and all-consuming. The sea “possesses and never relinquishes. It destroys but does not remember.” (D’Aguiar 210) The image of the sea ingesting Black bodies, a sea that “boiled with the bodies of Africans” (177) and made their bones crack and splinter has a crypt-like quality which silences the voices of the unnamed slaves entombed alive. Unable to either return to the shores or be fully consumed by the sea, the memory of these black bodies in distress lay in the Middle Passage, suspended in time and space.

The temporal resonances of the sea and its intense metaphoric quality makes the waters of the Atlantic a timeless and liminal space. Numerous critics have described the middle passage as unending waters which transcended space and time for the enslaved, since “A life on water was no life to live, just an in-between life, a suspended life, a life in abeyance, until land presented itself and enabled that life to resume” (61). A quarter of the slaves who were forced to undertake the journey never completed it. Alienated from their past and estranged from a future that never came to be, their absent presence metaphorically haunts the seas for posterity, constructing an image of the Middle Passage as the alpha and the omega, the “beginning and the end of everything” (112). The enslaved folk were deprived of a burial in their ancestral lands and were unceremoniously interred in the ocean. The lack of mourning and possibility of non-remembrance reduced these nameless entities to “souls that roam the Atlantic” (4) in a state of non-being, who were doomed to haunt the seas of the Middle Passage in an eternal limbo.

Afro-Caribbean diasporic narratives of trauma involve an obsessive re-membering of the past as a symptom of prolonged cultural amnesia. For this reason, the sea can be described as a Lieux de memoire, a site of memory for generations of Afro-Caribbean diaspora and the victims of the Transatlantic slave trade. Pierre Nora describes sites of memory as spaces of “increasingly rapid slippage of the present into a historical past” where memory “crystallizes and secretes itself” (7) These sites of historical continuity are unique as they represent a memory which is an actual phenomenon, “a bond tying us to the eternal present” (8) rather than history, which is a mere representation of the past. The geographical space of the sea is transformed into a historical site charged with memory and trauma, and becomes the “ultimate embodiment(s) of a memorial consciousness that has barely survived in a historical age that calls out for memory because it has abandoned it” (12), as described by Nora.

There is an extended emphasis upon the materialization of memory in the form of archives in the text. Pierre Nora talks about how modern memory is archival in nature and relies entirely on the “materiality of the trace” (13). Mintah’s account and Captain Cunningham’s ledger act as traces of material memory in the text that are eventually rejected. Mintah’s written testimony is dismissed by the court as “penned by a ghost” (169), while the captain’s ledger fails to take into account the full spectrum of the slaves’ suffering. The failure of material memory in the text then triggers a lacuna of a lieux de memoire, which is then filled by the seas of the Middle Passage. Consequentially, the seas of the Middle Passage present themselves as a site which is “mixed, hybrid, mutant, bound intimately with life and death, with time and eternity enveloped in a Mobius strip of the collective and the individual, the sacred and the profane, the immutable and the mobile.” (19) As a space invested with the symbolic aura of imagination, the topographical site is imbued with the memory of loss due to the specificity of its location.

With its “limitless capacity to swallow love, slaves, ships, memories” (27), the sea of the Middle Passage was a cold, passive spectator to the suffering it witnessed. Rehousing the victims in its watery depths, the site is best remembered as an open gravesite of mass burial at sea. However, today the Middle Passage erects itself as an eternal monument to the tarnished and bloody legacy of slave trade possesses the diasporic imagination to this day and colors contemporary art, literature, music and popular culture.

1 As cited in Carabi’s interview with Morrison

Works Cited

- “Fred D’Aguiar and the Memorialisation of Slavery.” Caryl Phillips, David Dabydeen and Fred D’Aguiar: Representations of Slavery, by Abigail Lara Ward, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2011, p. 151.

- Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux De Mémoire.” Representations, University of California Press, 1 Apr. 1989, https://online.ucpress.edu/representations/article/doi/10.2307/2928520/82272/Between-

Memory-and-History-Les-Lieux-de-Memoire. - Carabi, Angels. “Conversation with Toni Morrison.” Belles Lettres, vol. 9, no. no. 3, 1994, p. 38.

- Chassot, Joanne. “Tracing the Ghost.” Ghosts of the African Diaspora: Re-Visioning History, Memory, and Identity, Dartmouth College Press, Hanover, NH, 2018, p. 3.

- D’Aguiar, Fred. Feeding the Ghosts. Ecco Press, 1999.

- Hyppolite, Joanne. “Interview with Fred D’Aguiar.” Anthurium A Caribbean Studies Journal, vol. 2, no. 1, 2004, p. 4., https://doi.org/10.33596/anth.11.

- Mbembe, Achille. “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits.” Refiguring the Archive, 2002, pp. 19–27., doi:10.1007/978-94-010-0570-8_2.

- Pichler, Susanne. “’The Sea Has No Memory’: Memories of the Body, the Sea and the Land in Fred D’Aguiar’s Feeding the Ghosts (1997).” Acta Scientiarum- Human and Social Sciences, vol. 29, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1–14.