The relationship between memory and landscape is often overlooked, especially while examining the impact of environmentally induced distress on people. Traditionally, grief, trauma and nostalgia were attributed to human losses in socio-political violence. But it is equally imperative in case of individual/communal memory and other emotional tribunals of natural disaster victims and climate refugees. Their longing for a previously existed landform is seen outside the realm of the grievance hence, remain largely unspoken and undertheorized. As individuals and communities experience immediate or gradual transformations of the land, memory emerges as a valuable resource for navigating and responding the changes (Cruikshank 2005). This study underscores future research endeavors in the realm of landscape and memory which are surely topics independently worthy of study. But studying both in tandem elucidates the intertwining threads that bind realms of personal meaning and environmental catastrophe along with the processes of adaptation, preservation, and erasure of memories.

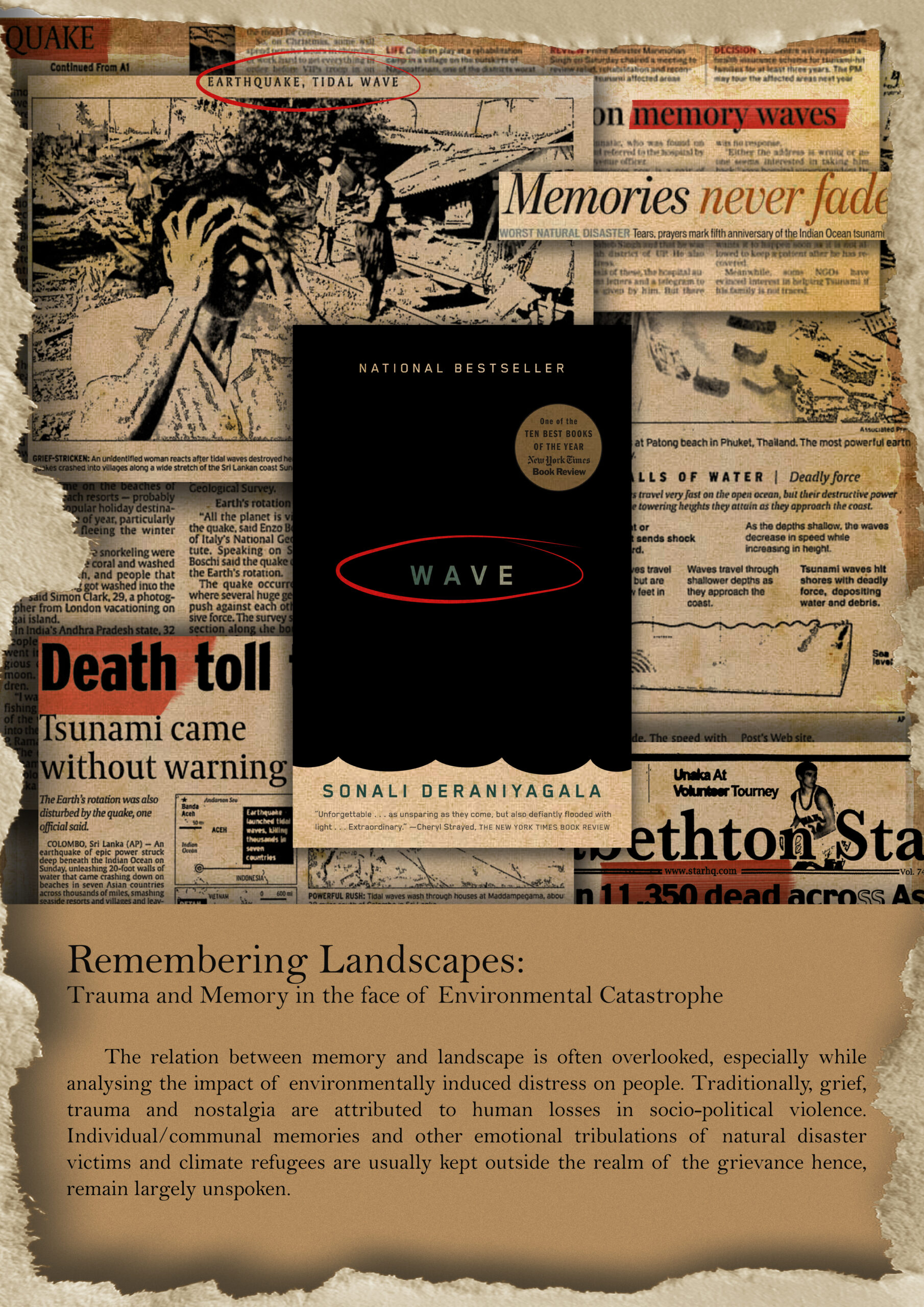

Sonali Deraniyagala’s Wave: A Memoir of Life After the Tsunami (2013) expounds on the trauma and estrangement encountered by the author after a narrow escape during the tsunami on 26th December 2004. The memoir asserts that the aftermath of environmental disasters can take a toll on human mental health and the obliteration of a landscape and memories associated with it would disconnect one from their existing identity. The author was born and brought up in Colombo, and was acclimatised to its seashores. Beaches were a place for pleasure and relaxation for her family, even after she moved to the UK. When the tsunami struck the Srilankan coast, she was at the beach hotel on vacation with her parents, husband Stephen Lissenburgh and kids Vik and Malli. Her recollections of the sea before the waves were warm, sunlit and delightful. She says,

We were frequently on the beach. Vik and I would walk on the empty morning sand to watch arrack-breathed fishermen draw in their nets as the crowd went wild. Steve made sashimi with the freshest tuna that was just o the boat, he relished that, proclaiming it “the dog’s bollocks”. (Deraniyagala 92)

…memory of us on a beach, eating gunnysack loads of mussels, steamed only in their own juices on an open re. The clatter of slurped-out shells on a tin plate, salt on the children’s eyelashes, sunset. (93)

After the disaster, she saw the sea and waves as evil, treacherous and horrifying and staying in Colombo became bewildering and chaotic. As Anne Whitehead writes, “fragments of the past” are not only located in the remnants or belongings of the dead but also “in nature and the landscape”(57). Since the landscape drastically changed after the tsunami, she couldn’t connect with the place anymore. She puts her dilemma thusly,

Everything was one colour, brown, reaching far. This doesn’t look like Yaala, where the ground is dry and cracked and covered in green shrub. What is this knocked-down world? (5)

I stared into this unknown landscape, still wondering if I was dreaming, but feating, almost knowing, I was not. (6)

Even though the tsunami was preposterously destructive, unlike other socio-political causes of mass death, it left the survivors baffled about the causality of the distress. Deraniyagala says,

“It’s the biggest natural disaster ever. A Tsunami. Until now our killer had for me been nameless. This was the first time I’d ever heard the word”. (16)

As Kali Tal points out, “survivors emerge from the traumatic environment with a new set of definitions” (16). It is evident from author’s bitter and loathsome characterisations of the sea after the disaster:

I walked down to the ocean alone. It was June when the surf here is wild, I stared. These waves, this close. I stood there taunting the sea, our killer. (41)In these six years since they died, I’ve found it hard to tolerate this landscape. I spurn its paltry picture-postcardness. Those beaches and bays are too pretty and tame to stand up to my pain, to hold it, even a little. (105)

Our life is also kindled when I go back to our old haunts. I avoided these places until recently, and I insisted I’d never return. (82)

Even though the survivors depart from the old world, they often cannot leave behind the habits and attitudes ingrained by fear and persecution. The contemplation of landscape comes necessarily with a question of how and from where they look at the place (Whitehead 54). Evidently, the trauma of the tsunami and loss profoundly changed the position from which the author looks at the beaches. To be traumatised is “precisely to be possessed by an image or event” (Caruth 5). Throughout the text, the tide and the death of her family rattled like waves in her psyche.

Entitled Les Lieux de memoire, Pierre Nora identifies that certain key sites of memory can be invested with particular emotive and symbolic significance in the construction of identity. Examples of lieux de memoire include places, symbols, monuments, commemorative dates and exhibitions (xvii). In Wave, the author’s old house in Colombo, which was later sold to a Dutch family, was considered a monument of her pre-tsunami life with her kids, parents and husband in harmony with the sea. She says,

In Colombo, there is no home now, not even one empty of them. I want the solace of that space, and I feel dispossessed. When I go back there, I break into a cold sweat and become nauseated as I pass through our neighbourhood. It is unacceptable that I can’t drive through those gates and walk into my childhood home. I know every pothole on that street, my foot goes down on the clutch, and my hand changes gear with effortless recall. My memory of the house is immaculate. But I feel expelled from there. I lost my dignity when I lost them, I keep thinking. (63)

Memories have such an impact on a person’s “sense of place” that any catastrophe that disrupts or transforms a person’s life completely can result in social and psychological alienation from their surroundings and, ultimately, from their pre-disaster selves (Chaudari 271).

Here, in this ravaged landscape, I didn’t have to shrink from everyday details that were no longer ours […] My surroundings were as deformed as I was. I belonged here. (42)

I desperately shut out. I was terrified of everything because everything was from that life. Anything that excited them, I wanted destroyed […]At dusk I shuddered when I glimpsed the thousands of bats and crows that crisscrossed the Colombo sky. I wanted them extinct, they belonged in my old life, that display always thrilled my boys. (24)

Evidently, she dreaded everything that reminds her of the previous life. That included the sky, birds and the sea. She is not able to enjoy them as before as her violent, abrupt displacement from the “prima landscape” has traumatised her (Gayton 27). Hence, the sense of belongingness experienced by the inhabitants of a place depends on the objective manifestation of memories linked to the landscape (Proshansky 59).

For a person who have lived in close association with a landscape, the loss of familiarity can cause deep-seated psychological conflicts. In some cases, people associate their personal or social identity with the landscape. Any change in the existing condition of the landscape can shatter the connection between the individual and the place, leading to an adverse influence on the individual’s identity as well (Erikson 154). A close look at spatiality of environmental catastrophe, grief, trauma, and memory gives a new perspective through which ongoing hike in ecological disasters and resulting problems can be analysed. It also suggests the use of remembrance as a tool in bridging identity and a landscape among individuals affected by environmental catastrophe across the world. With the rising relevance of memory studies in contemporary academic scenario, this approach would bring such concerns to scholarly recognition.

References

- Caruth, Cathy. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. USA: JHU Press, 1995.

- Chowdhury, Indira. “Speaking of the Past: Perspectives on Oral History.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 49, no. 30, 2014, pp. 39–42. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24479737. Accessed 11 Jun. 2022.

- Cruikshank, Julie. Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. 2005.

- Deraniyagala, Sonali. Wave: A Memoir of Life After the Tsunami. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014.

- Erikson, Kai. Everything in its Path: The Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood. UK: Simon and Schuster, 1976, pp. 153-154.

- Gayton. “Landscapes of the Interior: Re-explorations of Nature and the Human Spirit”. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society Publisher. 1996.

- Nora, Pierre. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire. University of California Press. 1989. pp.7-24, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2928520?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents . Accessed 12 May 2022.

- Proshansky, H. M., Fabian, A. K., and Kaminoff, R. “Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self”. Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol.3, no.1, 1983, pp. 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-4944(83)80021-8

- Tal, Kali. Worlds of Hurt: Reading the Literatures of Trauma. USA: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Whitehead, Anne. Trauma Fiction. UK: Edinburg University Press, 2004.